WTF are Semantics?

If you spend even a little bit of time reading about or building distributed systems, eventually you come to understand that there are three types of message delivery guarantees:

- At-most once: Message delivery is not guaranteed.

- At-least once: Messages delivery is guaranteed with possible duplication.

- Exactly once: Message delivery is guaranteed with no duplication.

Ensuring that these semantics are met is a shared responsibility between the message queue – in this post, I’ll cover some popular AWS services – and the producer or consumer of messages (i.e. the application). You can, for example, achieve exactly once guarantees with an at-least once message queue if the consumer deduplicates messages.

Semantics in AWS Services

For the most part, people usually consider these semantics within the scope of the message queue (and not the application – but more on that below). This table describes the delivery guarantees for several AWS services:

| Service | At-most once | At-least once | Exactly once |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesis Data Streams | X | ||

| Data Firehose | X | ||

| EventBridge | X | X | |

| SQS1 | X | X2 | |

| MSK3 | X | X | X |

| MQ4 | X | X | X |

This list is not exhaustive, and there are caveats that make this more complex, such as:

- AWS services are often built on other AWS services, which has a transitive effect on delivery guarantees.

- Consumers, like AWS Lambda5, can introduce their own delivery guarantees.

Should You Care About Any of This?

If you don’t already know the answer to this question, then “probably not” is a good place to start. If you’re building a stock trading system, then yeah, you want that to process messages quickly, every time, and only once. If you’re building an event log or metrics collection system, then it matters much less if you lose a few messages or process some messages twice.

There are trade-offs with exactly once semantics – notably, they cause systems to run slower and be more expensive – so they shouldn’t usually be the default choice. In the case of duplicate messages, some downstream systems (like databases) can handle them depending on their design – for example, updating records instead of inserting them.

About Those Applications…

In almost all cases, if you want exactly once semantics then your application needs to be designed to handle duplicate messages. It doesn’t take much effort to find comments like this about service-level guarantees and real-world behavior:

AWS makes the same claim with FIFO SQS, and maybe I’m getting it wrong, but these claims 1) have a lot of caveats and 2) only work inside the boundaries of the messaging system. […] This leads to a situation where there’s a guarantee of exactly once acknowledgement, but not necessarily exactly-once processing or delivery. […] Systems claiming exactly-once lull developers into not planning for multiple deliveries on the subscriber, or the need to do multiple publishes, both of which can still happen.

– sudhirj (Hacker News, 2020)

Achieving Exactly Once Semantics in AWS

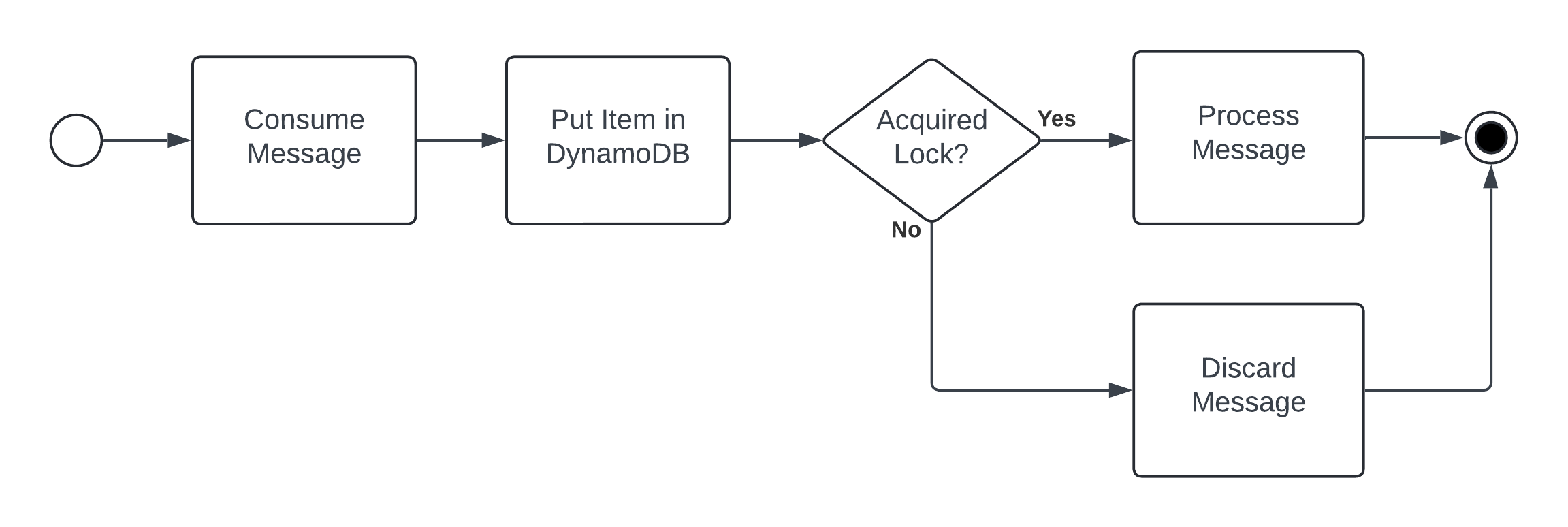

For the AWS services mentioned in this post, the most common way to solve this problem within AWS is to use DynamoDB as a distributed lock with an idempotency key. This works by:

- The app consumes or produces a message containing a unique value that is used to uniquely identify the message – this is the idempotency key, and examples can include a UUID or a hash of the message.

- The app uses the idempotency key in a

PutItemoperation in DynamoDB – this is the distributed lock. This operation has a constraint that the key must not already be in the table and an attribute that will delete the key after some time. - If the

PutItemoperation is a success, then the app processes the message; otherwise, the message is skipped.

As a block diagram, the process looks like this in a consumer app:

If you want to catch up on how to build an app with this type of logic, then I recommend reading the docs for and reviewing the code of the Idempotency feature of Powertools for AWS Lambda.

Is This Idempotency?

No, this is deduplication. Idempotent operations can be repeated without changing the result – for example, a PostgreSQL INSERT statement is idempotent if it uses the ON CONFLICT clause – but with this technique we discard duplicate messages, so it doesn’t matter if the proceeding operations are idempotent.

Does It Matter That This Isn’t Idempotency?

Probably not. In the context of delivery guarantees, the outcome is the same but the method used to achieve that outcome is different. People may use the terms “idempotency” and “deduplication” interchangeably when discussing distributed message systems, so it’s important to clarify the requirements of the system and its applications.

If you want to know more about how this can impact your service or app, then talk to a system architect or tech lead.6

When Everything Goes Wrong

This all sounds nice and simple, but eventually things will go wrong when an unexpected error occurs – exactly once semantics are difficult to implement reliably because they are so dependent on the behavior of your application and the architecture of your system. For example, you may need to consider:

- Is there a race condition when acquiring the lock?7

- What is the appropriate timeout, if any, for the lock?8

- How does the system behave under heavy load or backpressure?9

And the most important consideration: What happens next if message processing fails? At the point of failure, the message is already locked and can’t be processed again. You might consider:

- Skipping the message entirely.

- Now your exactly once system is an at-most once system, which is probably not what you want.

- Routing the message to a dead-letter queue.

- This allows a secondary – and possibly manual – process to handle the message.

- Retrying the message after waiting for some time.

- If each lock has a timeout, then processing can be retried after the lock expires.

In all cases you should have monitoring and alerting in place to detect when failures occur (because they definitely will occur).

Implementing Exactly Once Semantics

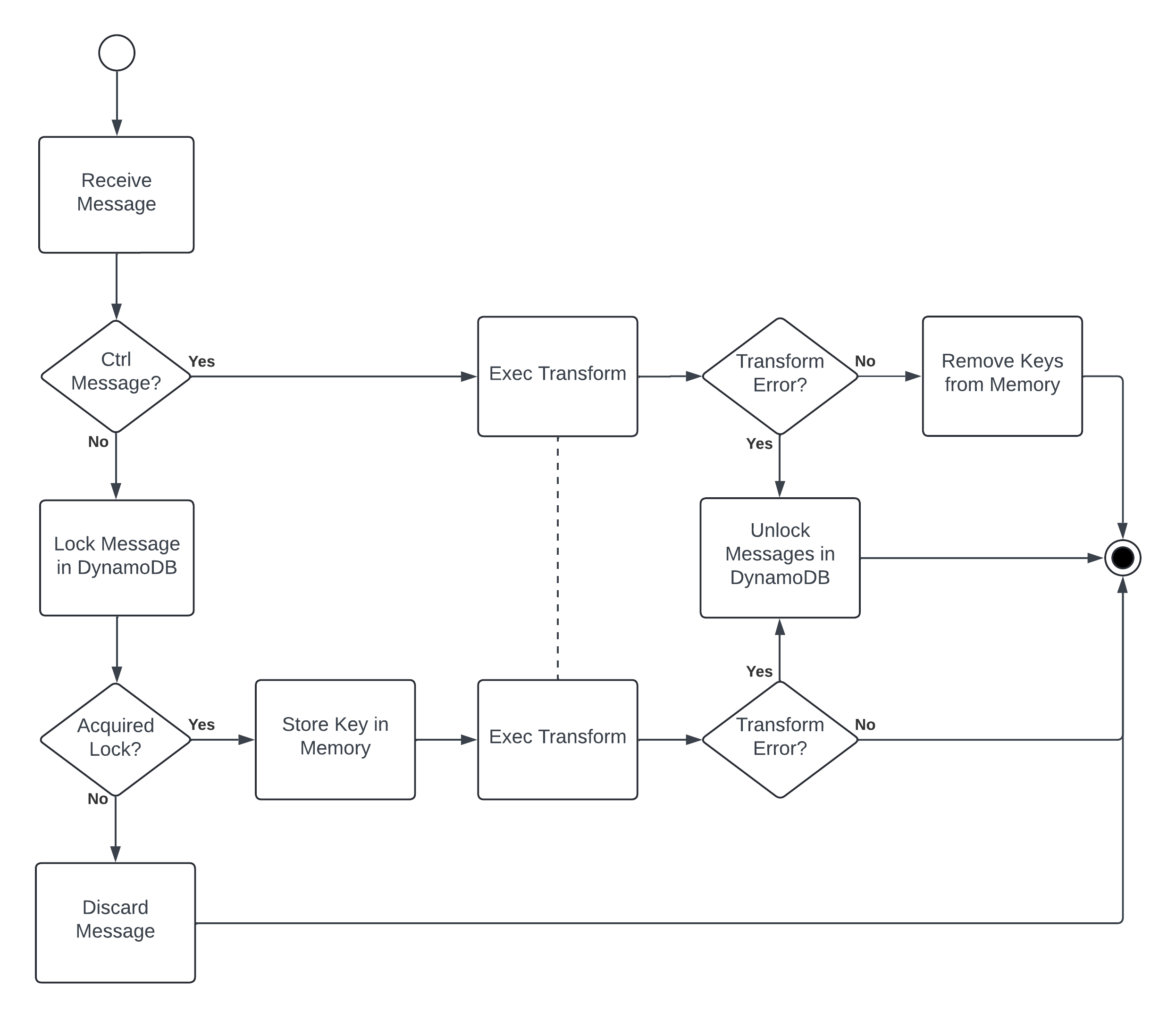

Recently, and for very bad reasons10, I added exactly once semantics to Kinesis, Firehose, and more via Substation with the inclusion of a lock transform. This was more troublesome than integrating a library like Powertools because Substation is fully configurable by users and it processes streaming data. The problem with implementing this in a streaming data processor is that errors can occur to a message after it is locked and successfully handled. Wait, what?

Here’s an example: in Substation every send transform (e.g. send to Kinesis, Firehose, etc.) batches messages and sends them as a single request; messages are considered “successfully handled” if they are added to the batch without error, but the result isn’t known until the batch is sent. If an error occurs when the request is sent, then we have a problem because locks are held for each message but the messages were not successfully delivered.

(In case you’re wondering, messages must be locked as they are batched, otherwise there is a risk that duplicate messages can be put into the same batch.)

Relevant to this problem, Substation is unique compared to other data transformation (or ETL) systems for two reasons:

- Transform state is always shared across many workers.

- Data flow is managed by unique messages known as ctrl messages, not the system itself.

This problem is solved by using ctrl messages as checkpoints to persist locks in DynamoDB. If any error occurs between checkpoints, then the locks are removed from DynamoDB so that the messages can be retried.11 It looks like this:

As a bonus, this design works with every Substation transform, not just ones that send data to a destination. This means that you can also use exactly once semantics to, for example, strictly limit how often your system calls an external API. In practice it looks something like this:

sub.tf.meta.kv_store.lock({

kv_store: kv, // DynamoDB table.

prefix: 'eo_system', // Optional prefix for organizing keys in the table.

ttl_offset: '1m', // Amount of time to wait before expiring the lock.

transform: sub.tf.meta.pipeline({ transforms: [ // The transforms to run exactly once.

sub.tf.send.stdout(),

] }),

}),

If the transforms inside meta.kv_store.lock fail, then the locks are removed from DynamoDB before the error is propagated to the caller.

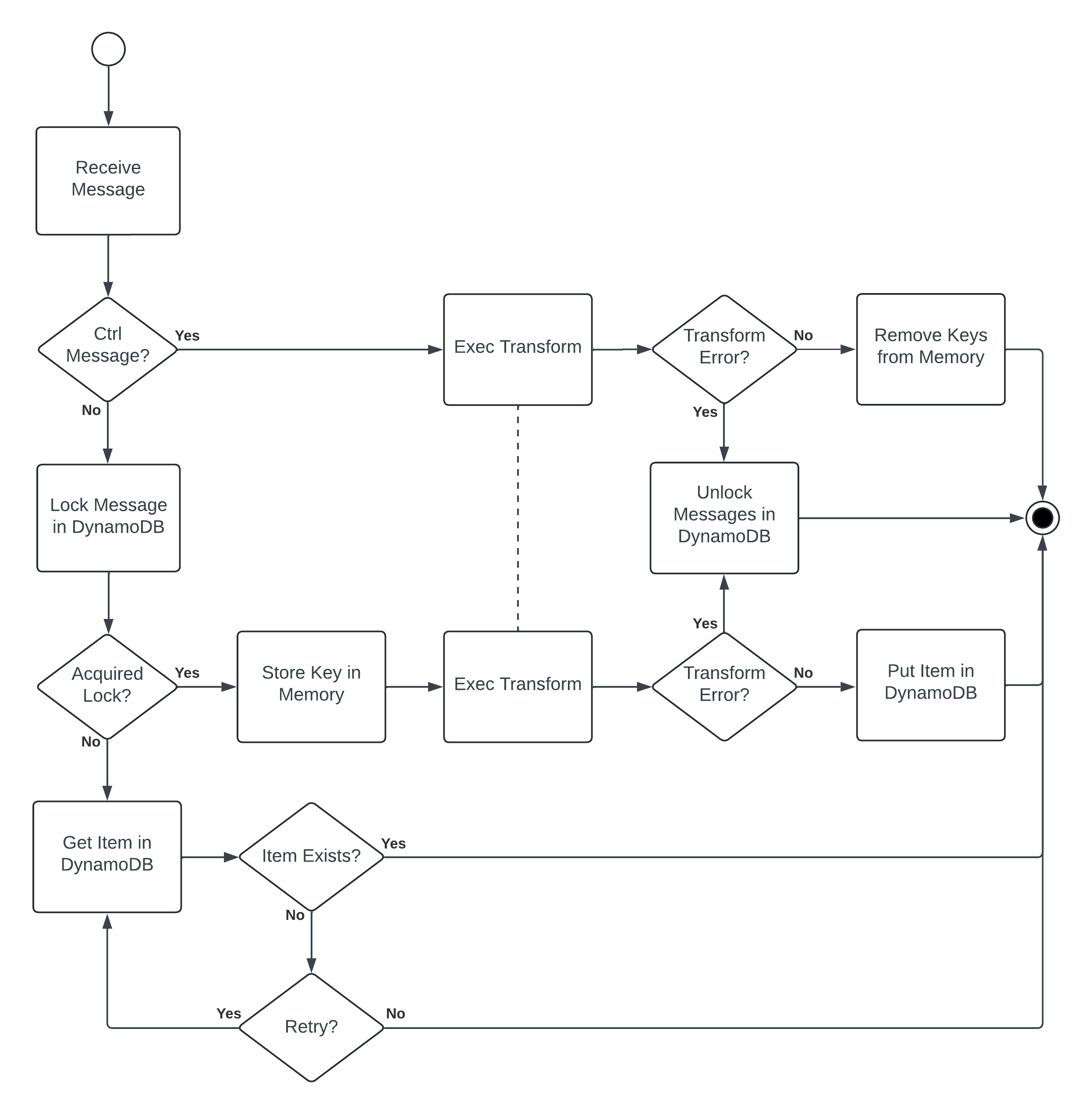

What About Idempotency?

But what if you want actual idempotent data transformation and not just deduplication? You can build that yourself using Substation’s other KV store transforms and a custom retry strategy. That looks like this:

Shocking to some, but all of that is configurable without touching any application code. This solution also has the side effect of applying backpressure if some data must exist before other data is processed, which might be useful (or not) on its own.

What Now?

I’ll say again that exactly once semantics increase costs and slow down systems, so they should be used only as needed, but if you need them in Kinesis, Firehose, S3, or other AWS services, then Substation is a good start. Otherwise, the methods and caveats described here (e.g. DynamoDB locks, Lambda Powertools, etc.) should be enough to help you get started.

Although not a message queue, SNS has the same delivery guarantees as SQS. ↩︎

SQS optionally provides exactly once semantics for a (non-configurable) period of five minutes. ↩︎

MSK is managed Kafka, which can be configured to provide exactly once semantics. ↩︎

MQ is managed ActiveMQ or RabbitMQ, which can be configured to provide exactly once semantics. ↩︎

More documentation should use WARNING labels like this. ↩︎

If you are the system architect or tech lead, then phone a friend. ↩︎

DynamoDB addresses this using conditional writes. ↩︎

DynamoDB uses time-to-live to expire items, but it comes with this caveat that can impact the behavior of your system: “DynamoDB automatically deletes expired items within a few days of their expiration time … expired TTL attributes may be deleted by the system at any time, typically within a few days of their expiration.” ↩︎

You should assume that backend services can fail at any time. You’re more likely to see failure as a result of service misconfiguration (for example, a misconfigured or poorly optimized auto scaling policy) than you are to see a service outage (DynamoDB has five 9s of availability). ↩︎

I wasn’t sure if it was possible, and wanted to see if it was. ↩︎

Substation also has strict error handling guarantees – errors are always propagated to the caller and the default behavior for an application is to crash – which signals to the caller that their message group needs to be retried. This works really well with batching AWS services like Kinesis that use continuous retry strategies and less well with asynchronous services like S3 that limit the number of retries (but that’s what dead-letter queues are for). ↩︎