Preamble

In October 2019 I joined the Splunk Global Security organization to build Splunk’s internal threat hunting program. Over a few months we went from an organization with no defined hunting program to one that can do full-scale, high-value hunting. This post describes how individual hunts can be structured to maintain focus and avoid “rabbit holes.”

Before diving into this topic, I recommend that you take a moment to watch this presentation from Justin Kohler and Patrick Perry – it covers some of the concepts described here.

Structured Vs. Unstructured Threat Hunting

Before we operationalized our hunting program, I spent a long time thinking about structured and unstructured hunting. At the time, I didn’t know what these terms meant, but I knew that most of the teams I’ve worked on were less effective than they should have been due to a lack of structure. These are the “structured” characteristics that I wanted our program to have:

- Task-driven and focused: Hunt analysts actively recognize and avoid “rabbit holes.”

- Organized: Hunt analysts practice strong “mise en place” and follow documentation standards.

- Adheres to schedule / priorities: Hunt analysts have dedicated time for hunting and assess risk before acting.

Conversely, these are the characteristics of an “unstructured” hunt program:

- Curiosity-driven and easily distracted: Hunt analysts do not recognize and regularly trip on “rabbit holes.”

- Disorganized: Hunt analysts practice weak “mise en place” and follow no standardized documentation model.

- Lack of schedule / priorities: Hunt analysts have no dedicated time for hunting and chase threats that are “new and shiny.”

There are a few things to note about these characteristics:

- Structured programs should be more effective, reliable, and predictable than unstructured programs.

- Unstructured programs can produce impactful results, but they do it less effectively than they otherwise could.

- Programs can have a mix of structured and unstructured characteristics – there is always room for improvement.

In practice, building a structured hunting program meant that we needed to clearly understand the processes and procedures that would make us successful.

Task-Driven Hunting

A significant “aha” moment for me during this journey was identifying the need to practice task-driven hunting. Task-driven hunting is a strategic approach to hunting where individual components of a hunt become tasks for analysts to complete. In hunting, we often use hypotheses to guide our analysis; task-driven hunting enumerates the steps required to prove or disprove a higher-level hypothesis.

Here’s an example: let’s pretend that we want to hunt for evidence of the MINEBRIDGE backdoor in our corporate environment. Our source is a blog post from FireEye that describes a variety of delivery, installation, and command and control techniques. Tasks involved in hunting for a MINEBRIDGE compromise could include identifying the following:

- Phishing Emails Sent via Acelle

- Phishing Emails Use a Tax Theme

- Office Documents Leverage VBA Stomping

- Zip Files Written to TEMP and Deleted

- DNS Queries to .top TLD

These tasks are not inclusive of all possible tasks, but as an example, they cover techniques across delivery (KC3), installation (KC5), and command and control (KC6).

Here’s what makes structured hunting effective: we define these tasks, document them, and assign them to analysts. We’ve had hunts with one or two tasks (completed within hours) assigned to a single analyst and hunts with 15 to 20 tasks (completed within weeks) assigned to a group of five analysts. By spending more time up front planning our hunts, we have greater flexibility to execute on them.

Task-driven hunting achieves the first characteristic of a structured hunting program: tasks keep analysts focused and help indicate when they are getting off-track (i.e., avoiding “rabbit holes”). An analyst focused on a task named “Phishing Emails Sent via Acelle” knows what they should be looking for (Acelle SMTP header artifacts) and what they shouldn’t be looking for.

A common pitfall hunting analysts fall into is identifying intriguing but irrelevant artifacts, pivoting their analysis to them, and losing focus of the original task. In a task-driven hunting program, we ask analysts to note the intriguing artifacts (this is a “finding”) and continue with their initial task; when the task or hunt is complete, we review the findings and use them to create new tasks or hunts.

Operationalizing Task-Driven Hunting

We use Jira to operationalize our task-driven hunts, but any hierarchical ticketing system should work. Here are the rules we use:

- Threat hunting operations have a unique Jira project (e.g., “HUNT”).

- Jira project uses Kanban, not Scrum (depends on the size of your team, Kanban works best for us).

- Jira tasks represent a single hunt that is ready for execution.

- Jira sub-tasks represent a single task associated with the parent hunt.

- Jira stories are external requests for a hunt; when they are ready to be hunted, stories convert to a Jira task.

- Jira epics represent a collection of related hunts.

- Jira labels are used to tag hunts with auditable data (more on this below).

- Jira time tracking is used to track how long tasks take to complete.

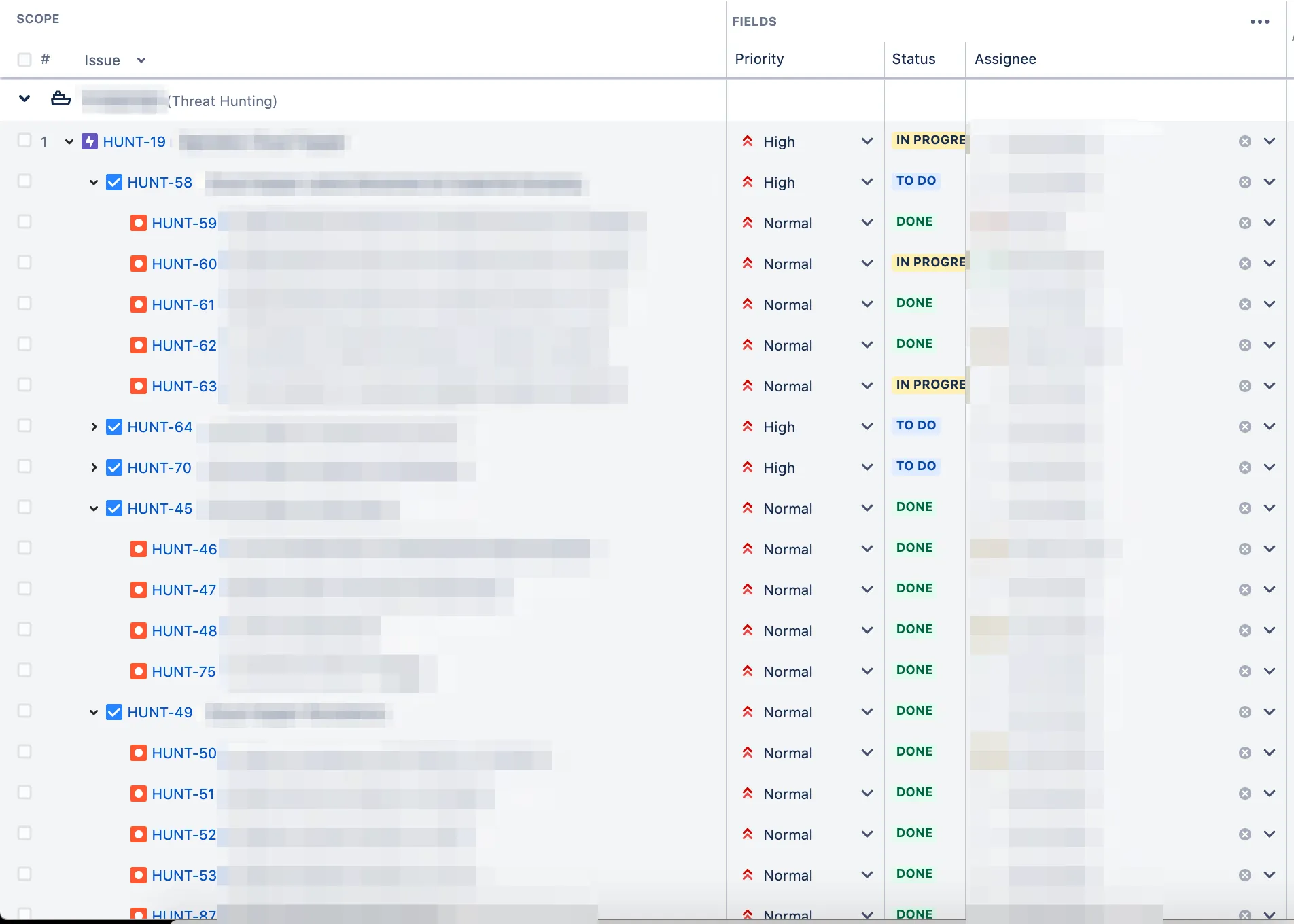

Here’s an example of using epics, tasks, and sub-tasks: let’s pretend that we want to hunt for evidence of an open-source post-exploitation (KC7) framework in our environment. The framework contains 14 individual modules spread across multiple ATT&CK tactics (e.g., discovery, persistence, privilege escalation, etc.).

Due to the scope of work (since we time track our tasks, we know that the average task aligned to KC7 takes 6 hours to complete), we determine that it should be a Jira epic. Assigned to the epic are individual hunts (Jira tasks) divided among the ATT&CK tactics present in the framework. Attached to each hunt are hunt tasks (Jira sub-tasks) aligned to the 14 modules; each hunt task focuses on identifying the presence of a single module in our environment.

Here’s how this appears in the Jira hierarchy:

- 1 epic (“exploit_framework_x”)

- 3 tasks (“Discovery of Exploit Framework X”, “Persistence of Exploit Framework X”, “Priv Escalation of Exploit Framework X”, etc.)

- 14 sub-tasks (“Exploit Framework X Module 1”, “Exploit Framework X Module 2”, “Exploit Framework X Module 3”, etc.)

Here’s a redacted screenshot from our Jira portfolio of this in practice:

An analyst’s ability to participate in hunting scales with experience:

- Junior analysts may complete hunt tasks, but are unlikely to define them.

- Analysts may complete and help define hunt tasks, but are unlikely to define hunts or epics.

- Senior analysts are expected to complete and fully define hunt tasks, hunts, and epics.

This methodology provides many operational advantages, including:

- Hunts scale across any number of analysts.

- Analysts are focused on tasks and are not required to understand the full context of a hunt.

- Analysts can join and leave a hunt at any time (as long as they have the time to complete a single task).

- Impactful discoveries get reported as tasks are completed, lowering our “time to action” findings.

- Team understands the level of effort involved in executing specific hunts.

Next, let’s talk about Jira labels; key-value Jira labels power our strategic operations. Below is the labeling schema we use for our hunt project:

ATTCK-- Maps to ATT&CK framework tactics and techniques, such as ATTCK-TA0003, ATTCK-T1156, etc.

CKC-- Maps to the Kill Chain, such as CKC-3, CKC-6, etc.

ENV-- Maps to a business environment, such as ENV-Corporate, ENV-Cloud, etc.

TA-- Maps to a named threat actor, such as TA-TA505, TA-CozyBear, etc.

MAL-- Maps to a named malware, such as MAL-Emotet, MAL-TrickBot, etc.

DATA-- Maps to a hunting dataset, such as DATA-Network, DATA-Host, etc.

TECH-- Maps to a hunting technique, such as TECH-Searching, TECH-FreqAnalysis, etc.

These labels fuel our metrics and keep us honest about what we are hunting, where we are hunting, and how we are hunting; they make it easy for us to determine if we are biased toward particular techniques, threat actors, and datasets. The operational overhead of tagging hunts and hunting tasks is low compared to the value we get out of tracking this information (i.e., the return on investment is good).

Finally, let’s cover Jira links; links are a method of tying two Jira stories together and they’re an important tool that we use to show our organizational impact. For hunting operations, we use the causes / caused by link.

Actionable findings are documented as new Jira stories for teams that are impacted by the finding; when this happens and we link them together, they look like this in Jira:

HUNT-NNNcausesFOO-NNNFOO-NNNcaused byHUNT-NNN

Links remove ambiguity about what our program is doing and how successful it is; they also make it easy to create detailed tables and visualizations of our impact on the organization and check on the operational status of our findings (“what has the impacted team done with our finding?”).